This fall, Grace Farms Foundation’s Justice Initiative Director Rod Khattabi and Deputy Justice Initiative Director and General Counsel Alina Marquez Reynolds, co-authored an article with Mathew Chemplayil of the Equanimity Foundation that was published in Equanimity Foundation’s Inclusive Discourse. In recognition of National Slavery and Human Trafficking Awareness Month, we share it here.

“Corporations place their economic interests at the forefront of their activities, and while they may have ethical or moral stakes in combating trafficking, no action will be taken unless it is deemed beneficial to the bottom line. Speaking from his own experience working with corporations, Mr. Khattabi states, “the CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility [programs]) in those companies … all want to do the right thing. But at the end of the day, they’re looking at the bottom line – the profits. Corporations look at the profits…” – Rod Khattabi

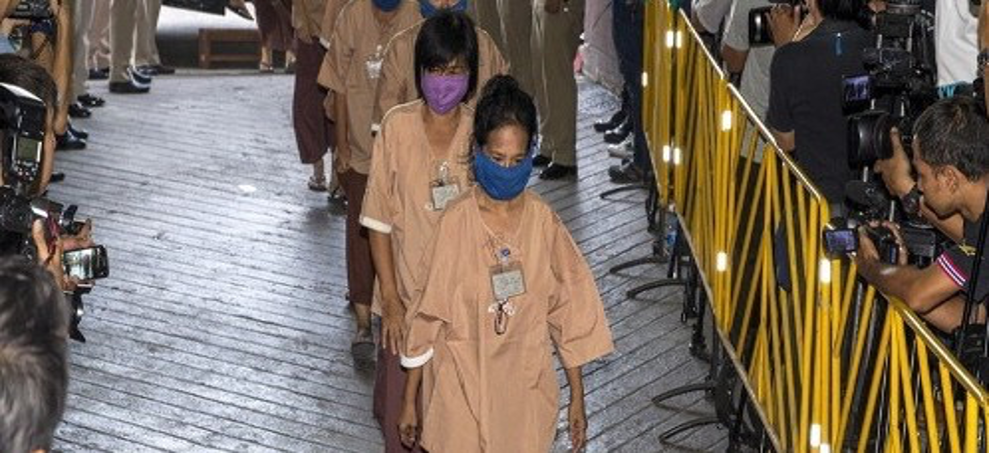

Human trafficking is a $150 billion global business that affects more than 25 million people worldwide. [1] Many victims of human trafficking regularly interact with the public, but fear and trauma often prevent them from speaking out about the abuse they face. Since many people unknowingly encounter victims, human trafficking is often described as a crime that is hidden in plain sight. The general public is largely uninformed of the warning signs of exploitation. People also tend to be unaware that some of the food and goods they purchase are made by trafficking victims trapped in cycles of abuse. In this Equanimity Foundation Inclusive Discourse (EQF ID) piece, we examine the challenges associated with combating human trafficking, approaches used to find justice for survivors, and a call-to-action for everyone to employ strategies to fight against modern day slavery.

The United Nations (UN) defines human trafficking as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit.” [2] Human trafficking is a widespread practice that spans across the globe and affects individuals of different ages, races, and genders. The practice is prevalent in many labor-intensive and under-regulated industries ranging from agriculture to manufacturing and takes a variety of forms such as debt bondage, domestic servitude, and sexual slavery. [3]

Although efforts to stop human trafficking have existed for decades, the fight against it has been limited by a plethora of factors. For example, as a phenomenon that often spans across nations, finding perpetrators can require legal cooperation between multiple countries’ criminal justice systems, each with their own cultural norms and labor practices. While many nations are willing to publicly state their opposition to human trafficking, few are willing to address the sociopolitical stigma associated with it. Many countries also fail to allocate the resources and reforms needed to properly support law enforcement efforts to combat these crimes, such as by creating “gender desks” where victims can report gender-based violence, sexual abuse, and trafficking crimes to police. [4]

As noted by Human Rights Watch, governments struggle to work together against human trafficking because of “coordination challenges, logistical difficulties, language barriers, political dynamics, corruption, and apathy about violence against women.” [5]

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has stymied some governments’ efforts to combat human trafficking. It has deteriorated the social support networks and economic safety nets of underserved communities, making them more susceptible to traffickers who lure victims with promises of financial remuneration.

The pandemic has also accelerated the shift toward a more digital world and changed consumer behavior to work, shop, and seek entertainment online. As cyberspace is used at a higher frequency, sexual predators are taking advantage of web content proliferation and poverty to access vulnerable children.

Incidents of Online Sexual Exploitation of Children (OSEC), which involve the production, possession, and distribution of child sexual abuse materials and livestreaming of sexual abuse or exploitation, have increased dramatically during COVID-19. [6] For example, as restrictive quarantine measures were imposed and families’ income decreased, indigent families began selling their children to human traffickers. Consequently, the Philippines experienced a threefold increase in OSEC crimes. The UN’s 2020 report on Human Trafficking notes that factors such as poverty are important to consider in human trafficking cases because victims are often targeted when they are in vulnerable positions. [7] The pandemic has also challenged the ways in which law enforcement officials combat human trafficking. The U.S. Department of State’s 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report indicates that governments have been forced to reallocate resources to areas such as health services, and lockdowns make it difficult for law enforcement to conduct field work and hold legal proceedings. [8]

As the ability to investigate and prosecute these cases is hampered, one significant way to combat human trafficking is by embracing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a deterrent strategy. Multinational corporations can ensure their supply and labor chains follow ethical standards but may not always be motivated to end these practices unless consumers and human rights groups apply pressure for them to act responsibly.

Demand for CSR has increased in part due to criticism of more traditional, law enforcement-led approaches to combat human trafficking, which focus on finding and prosecuting criminals. Critics of the prosecution approach argue that it has limited success in stopping human traffickers and law enforcement officials often treat victims like criminals, deterring many victims from coming forward because they fear facing criminalization. [9]

A case study of corporate social responsibility that Equanimity Foundation (EQF) has experience with is that of foreign migrant household workers (FMHWs) in southeast Asia. Job placement agencies work across international borders to recruit staff (who are primarily women) in poorer countries such as the Philippines, Cambodia, and Laos and relocate them to locations with wealthier economies such as Singapore and Hong Kong.

These job placement agencies primarily serve wealthy American and European expatriates living in Asia. FMHWs account for a substantial sector of regional economies. There are approximately 247,000 household workers in Singapore and 370,000 in Hong Kong. [10, 11]

Working conditions for the sizable FMHW population are often unethical with many workers facing physical and emotional abuse as well as unfair payment contracts. In addition, apathetic attitudes toward the plight of migrant women workers leads to a dearth of support and lack of protection for women who try to escape abusive labor conditions. [12]

Enforcing fair labor practices is also challenging because many workers are obligated to reside in their employers’ homes, making it difficult for them to report abuse. [13] Job placement agencies exacerbate the abuse by levying exorbitant ‘recruitment fees’ on FMHWs. As a result, FMHWs are forced to take pay cuts until their fees are paid off, leading to debt bondage and an inability to pay for their own expenses or send remittances. [14, 15]

EQF’s own research found that some FMHWs employers, such as American expatriate fund managers and corporate executives, may not always be aware of how job placement agencies abuse vulnerable populations by placing women into positions of debt bondage and denying adequate legal protection. Since many wealthy expatriates work for multinational companies with CSR programs, these programs can be leveraged to require their workers to treat FMHWs better and avoid interacting with abusive job placement agencies. Educating potential FMHWs employers about unfair labor practices can be crucial in making expats accountable. In this way, corporate social responsibility can be leveraged to pressure multinational companies to improve due diligence when hiring job placement agencies to help prevent their workers from actively contributing to a social injustice issue that primarily preys upon vulnerable women from destitute backgrounds.

To broaden effectiveness and impact, corporate social responsibility programs should seek opportunities to partner and collaborate with the public sector, including law enforcement agencies. A multi-faceted approach is critical. Prominent experts in the field of anti-human trafficking promote this more holistic approach that takes into consideration both law enforcement and corporate social responsibility strategies. Rod Khattabi, Chief Accountability Officer & Justice Initiative Director at Grace Farms Foundation, spoke to EQF about his recommended approach. With decades of experience in federal law enforcement, Mr. Khattabi has worked internationally to raise awareness about human trafficking and to train police forces globally to build capacity to investigate these crimes and hold offenders accountable. He maintains that law enforcement is an integral part of the fight against human trafficking alongside initiatives such as CSR.

In his view, law enforcement agencies do not fight against human trafficking for economic or publicity reasons, but rather because they have a public mandate to do so. In contrast, he believes that corporations in many cases have little incentive to enforce ethical labor standards unless doing so will meet consumer demand and help their profits. According to the American Bar Association, “CSR starts with a corporation’s economic interests and then moves through the legal, ethical, and philanthropic opportunities and concerns.” [16] Corporations place their economic interests at the forefront of their activities, and while they may have ethical or moral stakes in combating trafficking, no action will be taken unless it is deemed beneficial to the bottom line. Speaking from his own experience working with corporations, Mr. Khattabi states, “the CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility [programs]) in those companies … all want to do the right thing. But at the end of the day, they’re looking at the bottom line – the profits. Corporations look at the profits; it is what it is.”

While Mr. Khattabi believes law enforcement plays a key role in combating human trafficking, he also notes that agencies must reform their practice. Criticism of law enforcement agencies focusing more on prosecuting perpetrators than protecting victims is not unfounded. An example of this is that victims in certain jurisdictions may only receive assistance and freedom of movement if they agree to cooperate with law enforcement agents and prosecutors. [17] Mr. Khattabi adds that law enforcement agents must be specially trained to build trust with trafficking victims who, even at the time of arrest, are hesitant to cooperate with law enforcement. Through trauma- informed interviewing skills, law enforcement can protect against re-traumatizing victims. Court proceedings are painful for victims because they are required to recount and face questioning on their abuse. Police agencies have tried to respond to these issues. Within Mr. Khattabi’s own career, he notes how agencies have begun to adopt a more compassionate approach. This is not always an easy task. Victims may be groomed to distrust authority, face serious trauma, or fear that compliance with law enforcement could result in negative consequences for their loved ones at home. Law enforcement agents must be better equipped to respond to the complex issues and work with service providers and non-profits to provide victims with the support they need.

One way to provide relief to victims is through the exercise of sound prosecutorial discretion. Mr. Khattabi notes that agents and investigators must work hand-in-hand with prosecutors from the outset of an investigation. Mr. Khattabi notes that agents and investigators must work hand-in-hand with prosecutors from the outset of an investigation.

It is within a prosecutor’s discretion to decide whether or not to charge someone with a crime, who to charge and what charges to bring. To dismantle trafficking organizations, prosecutors focus on developing evidence to bring and prove charges against the leaders of the criminal enterprise and understand that trafficking victims should not be held responsible for crimes they committed at the direction and control of traffickers. For example, Mr. Khattabi notes that while guidelines may compel law enforcement agents to make an arrest, a prosecutor may use her discretion to dismiss the case, bring less serious charges, or enter into pre-trial diversion or accelerated rehabilitation programs. All of this ensures that law enforcement agencies use their limited resources to prosecute only those who have perpetrated acts of human trafficking and not needlessly punish victims.

Mr. Khattabi suggests that increased prosecutorial discretion, as well as sentencing discretion for judges, is a necessary part of improving the Nation’s approach to combatting human trafficking. There must be an emphasis on improving access to justice for trafficking victims. The criminal justice system must protect trafficking victims and provide a path for them to become survivors.

Embracing corporate social responsibility and compassionate law enforcement are undoubtedly steps in the right direction. At the same time, human trafficking remains an issue that requires attention and support from diverse actors. The U.S. Department of State promotes an inclusive approach to combatting human trafficking based on a “4P model: prevention, protection, prosecution, and partnerships.” [18] The partnership component of the 4P model, indicates that nonprofits, civil society, faith- based organizations (FBO), and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) play a significant role in raising awareness and providing survivors with much needed support.

Recognizing the important contributions nonprofits can make to combat human trafficking, at EQF we strive to develop projects dedicated to protecting victims of human trafficking and seek to raise awareness about practical actions people can take to fight this type of abuse. Our work has materialized in successful programs for impoverished women facing sexual and labor exploitation in Latin America. These activities have enabled us to support victims in vulnerable societal positions and work toward ending gender-based violence (GBV). EQF’s Preventing, Informing, Educating, and Countering Exploitation and Slavery (PIECES) program in Venezuela and El Salvador, have found that traffickers lure and then coerce vulnerable victims (often young women and girls) into prostitution by leading them to believe they are going to engage in legal work in the United States or Europe, but end up trafficked and sexually exploited in a foreign country without any social support networks. [19]

EQF has also sought to raise awareness through various platforms. For instance, as part of Human Trafficking Awareness Month, we hosted an event on “Leveraging Data and Analytics to Combat Human Trafficking.” During this event, we brought attention to the relationship between data analytics/new digital technologies and how these can be used to dismantle human trafficking rings. We also underscored the importance of lived experiences and amplifying the voice of trafficking victims.

Moreover, through our awareness raising event campaign, we explored how technology platforms can be used to trace supply chains and gather large data sets including specifics like the price a person is sold for, and where and through whom recruitment is performed. Digital tools can also help analyze where victim recruitment is taking place, which ports victims are transferred through, and airlines they are transported on. [20] Armed with this data, machine-learning techniques are applied to aggregate case data. [21] All this information can be gathered through NGOs, open- source news articles, court cases and crowd-sourced data through phone applications that allow anyone to submit suspicious activity anonymously and securely. [22] It is imperative for the global community to be informed of the evolving nature of trafficking, engage, and use the latest technology available to successfully identify, prevent, and mitigate trafficking cases.

While human trafficking is global in scope, we all have a role to play in diminishing this nefarious practice. One of the simplest actions we can take to combat this phenomenon, which is often hidden in plain sight, is acknowledging that it exists and informing ourselves about the process, and how victims are targeted. There are also other ways of becoming involved in the fight against human trafficking. For example, the State Department notes several options, including writing to elected officials, donating to relevant organizations, and reporting potential instances of trafficking to the authorities. [23] Mr. Khattabi adds that informed consumption is another effective way for everyone to do their part. Supporting brands that make an active attempt to combat human trafficking practices places pressure on multinational corporations that fail to meet consumer demand for accountability in global supply chains that potentially benefit from modern day slavery.

Mr. Khattabi also promotes using task forces to combat the issue. Domestically, these entities work across state lines to counter trafficking organizations and ensure that the fight goes on even as networks expand. Internationally, it is crucial for nations to cooperate on anti-modern slavery and anti-trafficking initiatives. They must be willing to share information regarding the actions of human traffickers. By doing so, law enforcement agencies can be more effective at identifying perpetrators, who would no longer be able to seek refuge in nations with lax regulations or weak rule of law. The disinterest of many governments in spending the resources necessary to fulfill such goals presents an opportunity for actors such as private citizens and NGOs to apply pressure toward the passing of these regulations.

To move is to be human, and our modern world is full of dynamism. For too many, however, their movements are ultimately not of their own will, and that is an issue that affects us all. Though human trafficking has historically been a difficult issue to tackle, changes in how we approach the problem show immense promise. With collective effort, we can all ensure a more responsive, inclusive, and sustainable world free from the shackles of modern-day slavery.

Footnotes:

1.“Polaris | We Fight to End Human Trafficking,” Polaris Project, accessed July 30, 2021, https://polarisproject.org/.

2. “Human Trafficking,” United Nations: Office on Drugs and Crime, accessed July 23, 2021, https://unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/human-trafficking.html.

3. “About Human Trafficking,” United States Department of State (blog), accessed July 23, 2021, https://www.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking/.

4. Rebecca Grant, “How To Get Women To Trust The Police? ‘Gender’ Desks,” NPR, August 15, 2018, sec. Women & Girls, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/08/15/638872938/how-to-get-women-to-trust-the-police-gender-desks.

5. Heather Barr, “Trafficking Survivors Are Being Failed the World Over,” Human Rights Watch, August 5, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/08/05/trafficking-survivors-are-being-failed-world-over.

6. “OSEC: A Modern Face of Human Trafficking,” World Hope, accessed August 19, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/osec-modern-face-human-trafficking

7. “Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2020,” United Nations Publication (New York: UNODC, 2020.)

8. “2021 Trafficking in Persons Report” (Washington, DC: United Stated Department of State, 2021), https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/.

9. Peter Williams and Philip Langford, “The Case for Perpetrator Accountability to Combat Human Trafficking,” Council on Foreign Relations (blog), July 15, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/blog/case-perpetrator-accountability-combat-human-trafficking.

10. “Foreign Workforce Numbers,” Ministry of Manpower Singapore, accessed July 30, 2021, https://www.mom.gov/sg/documents-and-publications/foreign-workforce-numbers.

11. Vivian Wang. “For Hong Kong’s Domestic Workers During COVID, Discrimination is its Own Epidemic,” The New York Times, May 18, 2021, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/18/world/asia/hong-kong-domestic-worker-discrimination.html.

12. “Access to Justice Often out of Reach for Migrant Workers in South-East Asia,” News, International Labour Organization, July 26, 2017, http://www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_566072/lang-en/index.htm.

13. Ann-Christin Herbe, “Singapore Domestic Workers ‘Suffer Exploitation and Abuse’ | DW | 28.03.2019,” DW.COM, March 28, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/singapore-domestic-workers-suffer-eploitation-and-abuse/a-480101632

14. Mei Mei Chu and A. Ananthalakshmi. “EXCLUSIVE U.S. to Downgrade Malaysia to Worst Tier in Trafficking Report – Sources,” Reuters, July 1, 2021, sec. Asia Pacific, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/exclusive-use-downgrade-malaysia-lowest-tier-trafficking-report-sources-2021-01-01/.

15. Herbe, “Singapore Domestic Workers ‘Suffer Exploitation and Abuse’ | DW | 28.03.2019

16. E. Christopher Johnson, Jr. “The Important Role for Socially Responsible Business in the Fight Against Trafficking and Child Labor in Supply Chains,” American Bar Association, January 22, 2015, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/publications/blt/2015/01/02_johnson/.

17. Peter Williams and Philip Langford, “The Case for Perpetrator Accountability to Combat Human Trafficking,” Council on Foreign Relations(blog), July 15, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/blog/case-perpetrator-accountability-combat-human-trafficking.

18. United States Department of State, “Four ‘Ps’: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, Partnerships,” n.d., https://www.ctcwcs.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/four-ps.pdf.

19. “Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2020,” United Nations Publication (New York: UNODC, 2020)

20. “It’s Time We Harnessed Big Data for Good,” World Economic Forum, accessed August 20, 2021, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/data-big-harness-good-human-trafficking-stop-the-traffic/

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. “20 Ways You Can Help Fight Human Trafficking,” Office to Monitor and Company Trafficking in Persons (blog), accessed July 29, 2021, https://www.state.gov/20-ways-you-can-help-fight-human-trafficking/.